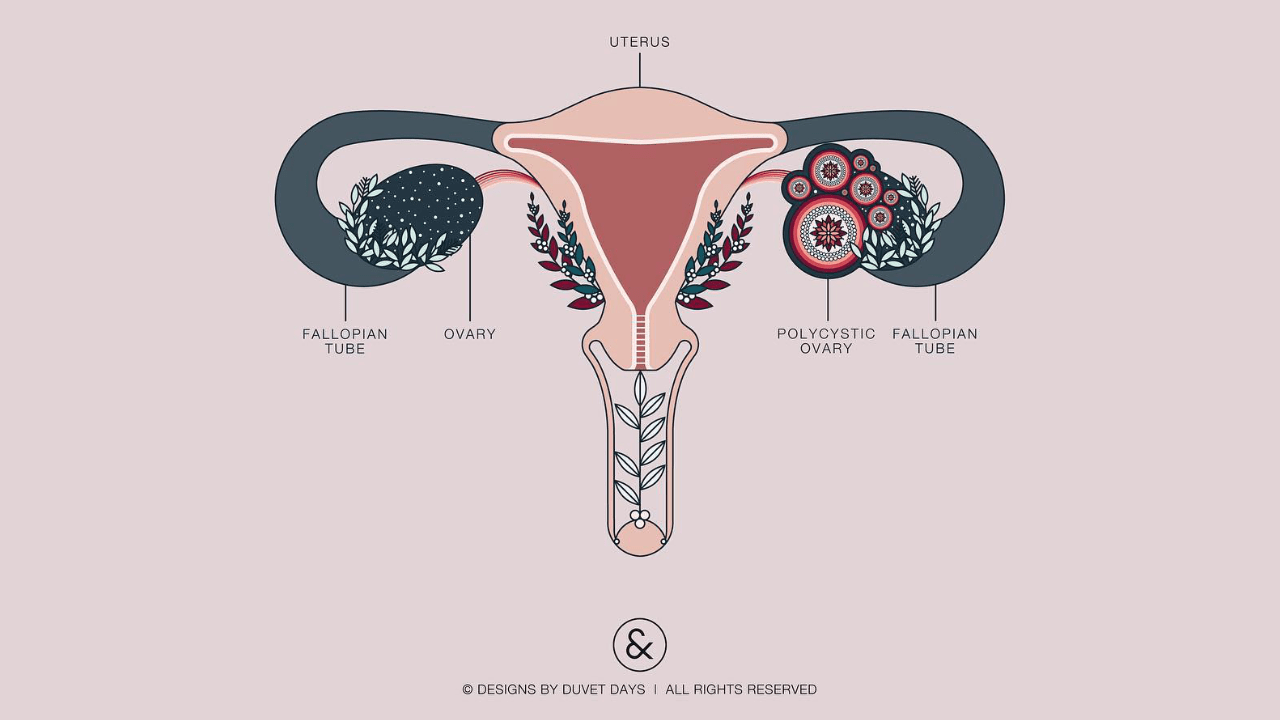

The main symptoms of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome are irregular menstrual cycles, gaining weight, excessive hair growth or hair fall, acne, dark patches of skin, inappropriate male features. PCOS is also usually detected during puberty, with the start of menses. This means – a girl who has PCOS might gain weight and will have a negative self-image in her teenage years.

Womxn with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome are at higher risk for binge eating behavior, having negative body image and depression and anxiety. Also womxn with PCOS have a higher prevalence for disordered eating than womxn without. It is clear that PCOD treatment should be done in a more holistic way paying careful attention to the mental health of the individual.

While women might be more likely to experience disordered eating – the risk of higher intensity and frequency (leading to eating disorders) is more in womxn with PCOS. According to an Australian study, binge eating was mostly noticed among womxn with PCOS.

For a teenage girl to go through so many hormonal changes as well as the judgements of society for having PCOS could be nothing less than traumatic. Girls with PCOS are told to lose weight and become more fit by doctors. While this is professional medical advice, this also means that the girl is forced to diet and exercise till she fits the ideal weight for her menstrual cycle to be regularised.

Now, apart from being told that no one will marry her because of her “extra kilos”, she is also told that not bearing children in the future is almost as good as never having a bright future. She is influenced and manipulated enough to start praying for her periods to become regular, and to lose weight. Strict diets, no junk food and a lot of exercise – not to become “fit” but to “get periods and bear children”. Again, this leads to an unhealthy relationship with food.

PCOS stays but the relationship with food deteriorates. While someone with PCOS can have regular periods- the danger of their cycle being irregular again always looms about their heads. Which means, the anxiety and stress remains and so does the rigorous dieting, exercising and guilt about eating food they like.

Disordered eating may be characterised by our self-worth being based highly (or exclusively) on body shape and weight, a disturbance in the way we perceive ourselves (like being thin and still calling ourselves fat), excessive exercise and diet routines and calorie counting, eating only certain foods with inflexible meal times and refusals to eat food outside.

Our preoccupation with eating and dieting might be so much that it adversely affects daily activities and may lead to maladaptive behaviour (like throwing up or using laxatives in order to remain in shape, also known as purging). Some might be in denial of the obsession with food, while others may talk about it more openly. Most of us don’t even realise how bad relationships with food can affect us.

Many eating disorders might be more visible to the eye and are diagnosed as ‘eating disorders’ when the frequency and intensity of these anxious thoughts and actions increase considerably in a span of a few months.